-----

A Book On Fire

The date is October 23, 1731, and words are burning. The Cotton Library, the world’s greatest collection of literature from the Middle Ages, has caught fire. Doctor Bentley, the library’s curator, staggers from the door clutching what might be the oldest, most complete copy of the Bible, dating from the 400s. That’s the book he’s chosen to save from the flames, but what has he left inside? Illuminated gospels, their magnificent pages covered in a thin layer of worked gold; a copy of the Magna Carta, some stories of the saints, histories of England, travel memoirs, poems, riddles composed by a long-dead wit … and the only copy of Beowulf.

Sir Cotton started his library when Henry VIII, he of the funny song and the many wives, impounded all the monasteries in England. Monks have a lot of books, but Henry was more interested in their money. The books went to Cotton, who suddenly became the owner of the greatest library in the English language. So he put all those books on shelves in a single big room and, to keep it all straight, he set busts of Roman emperors on each bookcase and labeled the books according to whichever marble head was looking down over them. Why use a boring decimal system or an online search engine when you can sort books by Julius Caesar, Caligula, and Vespasian? (While not an emperor, Cleopatra also had a bookcase in the library, and probably took some bitter pride in being the only woman in the room.) So there’s Augustus protecting the Magna Carta, Claudius with his copy of Genesis, Nero entrusted with the Lindisfarne Gospels and the only copy of the divinely haunting poem Pearl (perhaps Cotton felt Nero, more than anyone else, needed to get religion), and over in the case belonging to Vitellius – a heavy-drinking bum who shared his term as Emperor with a few others in the “Year of the Four Caesars” – on the top shelf, fifteenth book from the left, is the Codex we’re concerned with. The one that’s burning. I hope there’s nothing important in there.

To find out how Beowulf got into this kind of trouble, we have to go farther back. So keep your head down and don’t breathe the smoke. It is in the sixth century that the events of Beowulf take place; we only know this because he mentions a battle for which we have corroborating evidence. But although most of the action happens in Hamlet’s stomping ground of Denmark, the poem of Beowulf – and it really is a single poem, three thousand lines long – was told in northern England, two hundred years later, by Anglo-Saxons. These men didn’t consider themselves British; they were Viking through and through and their heroes were from the “old country”: Scandinavia.

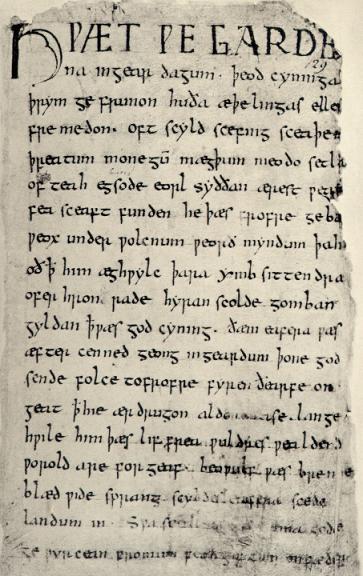

We don’t know the name of the guy who eventually wrote Beowulf down onto thin sheets of shaved leather, but once he did that version of the poem was copied and recopied by ink-stained hands from one book to the next for another couple of hundred years until, by sometime in the 900s, it was put together with a story of Saint Christopher, a collection of outlandish anecdotes about a Far East that no one had actually been to, a (supposed) letter from Alexander the Great, and a poem about Judith. (She’s the Jewish gal who cut off the head of her oppressor, Holofernes. I bet Cleopatra wished Judith was on her shelf.) All these pages were sewn together into a single book and, about six hundred years later, combined with yet another book before being slid onto the top shelf under Vitellius, where it is now burning – the edge of each page going black, erasing Beowulf and all his deeds from human memory forever.

About a quarter of the Cotton Library was burned up before the fire was put out. If you were an evil genius with a time machine and you wanted to destroy Western civilization, you might start by setting your flux capacitor for 1731, warming up Mr. Fusion, and lighting that fire. Or, if you are more criminally inclined, maybe you’ll go back and steal an ancient tome containing Secrets Man Was Not Meant To Know, setting the fire to cover your tracks. (Come to think of it, I don’t know you. Where were you in 1731?)

Even though Beowulf survived, his pages blackened but not burnt up, he did not fare well in the years that followed. Those who learned how to read the poem’s Old English were confused by what they found. Here was a tale both pagan and Christian, with children of Cain in it but no Christ. Its champions invoke God, but don’t seem very charitable, merciful, or least of all humble. Their virtues are heroic ones of courage, duty, and hospitality, loyalty to family and lord. Structurally, the whole thing doesn’t make much sense – it has three antagonists instead of one, with the last separated from the first two by a fifty-year gap. So is Beowulf two parts, or three? Filmmakers have been frustrated by that fifty-year gap all the way to the present day. Most simply ignore it.

Beowulf doesn’t rhyme; it alliterates instead. And no iambic pentameter is to be found because according to the Anglo-Saxon storytellers it didn’t matter how many syllables a line had as long as it was short and had three alliterations in it. To old white guys used to Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid, Beowulf just looked like bad poetry. And, worst sin of all, it wasn’t about high moral themes or the foundation of an empire, it was about a guy fighting monsters! Anything with trolls and dragons in it couldn’t possibly be taken seriously. The only people who could read Beowulf were scholars, and while they were too high-brow to say out loud that they considered it an inferior piece of crap, it certainly was no Iliad.

Enter JRR Tolkien. Yes, that Tolkien. The man who would go on to give us Aragorn, Frodo, and Sir Ian McKellan action figures happened to be one of those Ivory Tower Beowulf scholars and he didn’t just like the poem, he loved it. And like many of us who really love literature that critics despise, he came to its defense. In his 1936 essay Beowulf: The Monster and the Critics Tolkien wrote that the problem everyone was having with Beowulf wasn’t because the poem was bad, it was because everyone was trying to compare it to something it wasn’t – namely, Homer and Virgil. Beowulf didn’t conform to the rules of epic poetry because those rules were made up by ancient Greeks and Romans, not Scandinavians. The poem had a very solid meter, it just wasn’t one you counted in the traditional way. And that fifty year-gap between the fight with Grendel’s mother and the dragon? That gap was what made the poem so great. Beowulf is neither the story of a young hero who triumphs over monsters, nor the story of an old king who dies in a wasted effort to kill a dragon, but the combined tale of a man who, once young and impervious, advances with open eyes to his own inevitable and tragic death. You need both halves to make that story work. Tolkien’s reading of the poem woke everyone up to Beowulf’s hidden poetic mojo. Perhaps we should credit Tolkien with saving our book from that blazing library. It is no exaggeration to say that, without him, Beowulf would not now be read in high schools across America, would not be read by anyone except PhDs in medieval English, would not have films, novels, and comic books bearing his name.

Professor Tolkien didn’t just write about Beowulf; like a lot of good writers, he stole from it when he came to write his own fantasy masterpieces. After all, this was a guy who knew trolls and dragons were good stuff. In The Two Towers chapter “The King of the Golden Hall,” Aragorn and his companions arrive at the mead-hall of Meduseld, are stopped by a door-guard, forced to leave their weapons behind, and enter the hall only to be confronted by a white-bearded, helpless king and his weasely counselor. The entire episode is lifted straight out of the beginning of Beowulf, proving that even Oxford professors can swipe art. The name of King Theoden’s nephew Eomer appears in Beowulf, and Aragorn’s famous “Where is the horse and the rider?” poem, recited upon his arrival in Rohan, is actually another 10th century Anglo-Saxon song called “The Wanderer.” (These lines are given to King Theoden in Jackson’s film version.) The fire-breathing dragon of Beowulf, who sleeps on a mound of treasure underground but rises in wrath and anger after a thief makes off with a single object from his hoard, became the climax to The Hobbit (and countless fantasy imitators).

By the 1960s Tolkien was an American phenomenon and Beowulf had been translated into modern English more than once. So it comes as no surprise that John Gardner chose this material as the raw ingredients for his 1971 novel Grendel. Narrated in stream-of-consciousness style by the monster himself, Gardner’s is a book of existential philosophy with a little Marxist revolution and William Blake thrown in for spice. Grendel is fully intelligent and convinced that the world has no meaning, that life is just a continuous series of accidents without purpose or hope. He shouts at the sky, knowing the sky will not answer. He hunts Hrothgar’s men not because he hates them (and he does) but because he is hungry and bored. He consoles himself that by preying on these 6th century warriors, he is making them into heroes. He’s giving their universe meaning. When music, storytelling, and love threaten to impose a man-made meaning on his life, Grendel feels both fear and wrath. Eventually Beowulf shows up and rips our narrator’s arm off; the last thing we see is Grendel standing at the edge of Nietzsche’s abyss, staring into it. Gardner’s descriptions of the daily life of the Northmen (Grendel spies on them obsessively from cover of trees and cowsheds) are the best parts of the book. As odd as Grendel sounds, it was very influential and the first depiction of Beowulf on film is actually an adaptation of Gardner, not the poem. Grendel Grendel Grendel was an Australian-made animated feature in 1981 with the great Peter Ustinov supplying the voice of the monster/narrator.

Beowulf had gotten a larger audience, but to many it was still too boring for words – the perfect example of a literary work that no one would read by choice. Michael Crichton (he of Jurassic Park fame) felt differently and after a hot little argument with Professor Kurt Villadsen in 1974 he decided to show the world how interesting Beowulf could be. He did this by removing all the trolls and dragons, turning myth into the historical fantasy Eaters of the Dead. In this version of the story, Beowulf is a 10th century Viking accompanied on his quest by Ibn Fadlan, an Arabic traveler who really existed and whose travel diaries Crichton had read in high school. Instead of John Gardner’s emo Grendel we have the “wendol”, the last tribe of Neanderthals. They worship cave bears and eat anyone slow enough to get captured, maintaining their terrifying reputation by never leaving their own fallen behind and only attacking when they have cover from a black mist that blows down from the hills. In the poem, Beowulf (who Crichton names “Buliwyf,” and maybe that is my issue with the novel, because I cannot read “Buliwyf” without thinking of D&D’s Bullywugs, and now in my mind’s eye Beowulf is transformed Thor-style into a goggle-eyed toad) has to descend into a lake infested with sea monsters to kill Grendel’s monstrous mother, but here he rappels down a cliff to the sea-bound cave of an ancient woman with snakes in her hair. A dragon? Oh no: torch-bearing dudes on horses. This, children, is how everything fantastic, mystical, and awe-inspiring in the world is reduced by numbers to listless mundanity. Crichton wrote an interesting adventure story, but it’s no Beowulf.

It makes for good Hollywood though! Those of you paying attention can see by now that people don’t make movies based on Beowulf, they make movies based on books other people have written about Beowulf. John McTiernan’s version is The Thirteenth Warrior, a pretty solid adaptation of Crichton’s novel and probably Antonio Banderas’s Second Best Flick (for those keeping score: Mask of Zorro). Banderas’s ibn Fadlan is much more heroic than he is in the novel, kicking wendol ass with his scimitar of fury, though the dudes on horseback still don’t make a very convincing dragon. The haunted, distant, but Herculean hero called Beowulf is well presented in this film, and that’s why it rises above its source material. Crichton’s Scandinavian hero is foreign and remote; anyone trying to understand him may as well be reading Old English poetry. It’s more creative. But McTiernan gives us a man we can sympathize with, feel for, and admire, despite (maybe even because of) the way he distances himself from everyone close to him. He may not be mythical, but he’s real.

Thirteenth Warrior didn’t do especially well at the box office, but it was the opening shot in a firefight of Beowulf films which reminds me of nothing so much as the storm of Robin Hood movies which unjustly smothered Dave Stevens’ Rocketeer (but I’m not bitter). In the same year that it was released, 1999, we got a different version of Beowulf starring Christopher Lambert. Like Banderas, Lambert has done a very few good flicks (for those keeping score: Highlander) and a whole lot of really bad ones, and Beowulf is one the latter. A Road Warrior-style apocalyptic wasteland replaces 6th century Scandinavia in this version, probably because post-apocalyptic wastelands are notoriously cheap to film. Writer Mark Leahy plays fast and loose with the cast of the poem, keeping the character of Beowulf’s rival Unferth but changing his name to Roland because, well, one heroic poem is as good as another, right? (The Song of Roland is, of course, the national epic of France, and is a wonderfully good tragic poem in its own right about a different guy who goes up against overwhelming odds, triumphs for a while, and then dies. No relation.) The obligatory ginsu girl sex object is Hrothgar’s daughter Kyra. Everyone’s got a secret in this movie, though none of them are very interesting: Roland may have killed Kyra’s husband, Grendel’s mother seduced Hrothgar way back when and that’s where little monsters come from, and Beowulf himself is the son of Baal, “God of Darkness and Deceit.” (This explains his ability to regenerate from injury, but not his bad fight choreography.) Grendel’s mother transforms from a bottle-blonde vixen to a multi-armed fleshless spider-woman but, trust me, it reads a lot cooler than it looks.

Before Gaiman came to Beowulf, the last big-screen adaptation was Sturla Gunnarsson’s 2005 Beowulf and Grendel, starring Gerard Butler. Now, for hardcore fans of the monster-slaying Geat, this film is not bad. It’s got a realistic depiction of Viking life (complete with Sutton Hoo helmets for Beowulf and his buds) and is shot on location. Gunnarsson ditches the entire dragon encounter and, like Crichton and Gardner, humanizes Grendel into a sympathetic outcast, not a troll but an Andre-the-Giant-sized man who’s grown up in a cave with no company besides his old man’s skull – delivered unto him by Hrothgar at the film’s beginning. So Grendel’s murders are all justified, you see, and it isn’t until Beowulf and his men defile said skull that the kid gets really mad, leading to the armless slugfest, the attack of Grendel’s misshapen mom, and a climax which brings physical victory but moral and ethical compromise. Once he cut off the entire second half of the poem, Gunnarsson didn’t have a whole lot of story left, so he embroidered a beauteous red-haired witch (you thought the Marvel Universe had the trademark on those, didn’t you) who serves as love interest to both hero and monster. There’s really only two problems with Beowulf and Grendel. The first is the idea that a woman who has been raped would then befriend and protect her rapist; that just makes the back of my throat taste bad. The second problem is this: Batman: Year One is a great read, but it is ten times better if you can also read Dark Knight Returns. If Gunnarsson hadn’t amputated the poem’s payoff by ignoring the dragon episode, he wouldn’t be scraping so desperately to give Beowulf some meaning.

Earlier I said that Beowulf survived the inferno in the Cotton Library way back in 1731, that the fire was eventually put out. But I wonder if I wasn’t too hasty. Tolkien’s passion for the poem brought it to our attention in the first place, Gardner made a speechless monster into a long-winded philosopher, and Crichton and McTiernan tried to make it all real. This year there are not one but two film versions of Beowulf to come out in theaters (the other: Beowulf: King of the Geats). And it is exciting to see what Gaiman, one of comics most brilliant and creative writers, is doing with this deceptively-primitive tale. It seems to me now, looking back, that the fire is still raging inside Vitellius’ bookshelf. Flames are licking at the pages of Beowulf and we’re only now reaching out with our pink unprotected fingers, willing to be burned as long as we get a peek inside.